This blog post was written by our C4DT Digital Trust Policy Fellow, Leonila Guglya. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of C4DT or EPFL.

On 18 June 2023, the citizens of the canton of Geneva in Switzerland voted for the inclusion of a new fundamental right – the right to digital integrity, in the Constitution of the canton[1]. The new rules were accepted by all the communes (municipalities) without exception, featuring an overall cantonal average approval rate of 94.21%[2]. The digital integrity right is a significant global news item in the digital regulation realm, and hence deserves a closer look into its text, drafting history, possible geographical expansion, and potential implications.

Building on the information sourced from the relevant documents made public by the Canton of Geneva, such as the Report of the Great Council’s Human Rights Commission (personal rights) responsible for studying the draft constitutional law […] amending the constitution of the Republic and canton of Geneva (for strong protection of the individual in digital space) of 2 May 2022 and its annexes[3], as well as the Cantonal Explanatory Brief for the referendum of 18 June 2023 (part 4, pp, 44-51)[4], among others, this blog post is intended to offer an early assessment of the adopted rules.

The text

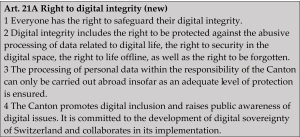

The text of self-standing provision put to vote at the referendum, which, ultimately, was accepted, includes 4 paragraphs. Besides supplementing the Constitution of the canton with the new fundamental right extending to natural persons only (as opposed to business entities) (Art. 21A, para 1), it also provides a non-exhaustive definition of “digital integrity” (Art. 21A, para 2), establishes additional guarantees for processing of personal data within the responsibility of the canton (Art. 21A, para 3), and includes the canton’s commitment to address the digital divide through promoting digital inclusion, raising public digital awareness, as well as an engagement in the development and implementation of Swiss digital sovereignty (Art. 21A, para 4) (Box 1).

Figure 1: The text of the new Art. 21A of the Constitution of Canton of Geneva, “Right to digital integrity”, author’s translation

Source: Cantonal Explanatory Brief for the referendum of 18 June 2023, supra note 4, p. 47

Reflecting the limited cantonal competencies with respect to regulating the private sector interactions[5], the responsibility for safeguarding this new fundamental right will fall on Geneva cantonal administration, the municipalities (“communes”), the autonomous public establishments, as well as to any other body of public law or private law responsible for carrying out tasks of cantonal or municipal public law[6]. No actionable private sector obligations (i.e. horizontal effect) are [yet] created.

At this stage, no implementing legislation is expected. It is anticipated, instead, that an inventory of the relevant existing laws with the view of their alignment with the new fundamental rights would be conducted[7].

The drafting history

A glance into the drafting history of the new set of rules, ensured in this section, could be helpful for better understanding of its origins and significance.

1. Chronology

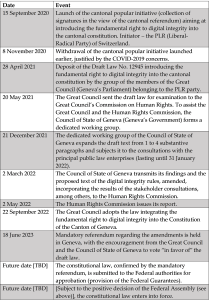

The steps already accomplished since September 2020, when the digital identity work has begun[8], and still on the agenda for the current text are mapped in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Emergence of Geneva’s digital integrity rules: Chronology

Source: Author, based on the Report of the Great Council’s Human Rights Commission (personal rights) of 2 May 2022 (supra note 3, varied instances), the Cantonal Explanatory Brief for the referendum of 18 June 2023 (supra note 4), and the Federal Constitution of Switzerland (Arts. 51 para 2, 163 para 2, 172 para 2, 186 paras 2 and 4, and 189 para 2)

2. The evolution of the draft text: a bigger picture

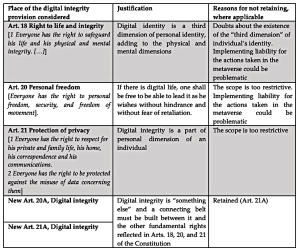

In essence, in slightly over 2 years of time, the language of the digital integrity rule has evolved from somewhat abstract single paragraph adding “digital integrity” (defined by one of the authors of the draft as “the [individual’s] ownership of the data ensuring that it does not undergo any accidental or unauthorized alteration during its processing, transmission or storage”[9]) to an integral part of Geneva’s Bill of Rights, a self-standing ad hoc text, putting forth not only the contours of the notion, but also mapping out several measures necessary for its realization (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The evolution of the draft text of the digital integrity provision

Source: Author, based on the Report of the Great Council’s Human Rights Commission (personal rights) of 2 May 2022 (supra note 3, varied instances), and the Cantonal Explanatory Brief for the referendum of 18 June 2023 (supra note 4, p. 47).

As visible from Figure 3, the place and the level of detail of the digital integrity provision have evolved through the drafting. Consideration of both elements might be of interest for understanding the reflexional process behind the new set of rules, feeding its future application and interpretation.

3. The place of the digital integrity provision among the other fundamental rights

Having investigated the 5 different options for placing the digital integrity text (Figure 4), the drafters conceded on the creation of the new, self-standing provision, linked to but not squared into the existing relevant fundamental rights.

Figure 4: Potential places for the digital integrity language in the Geneva Constitution’s Bill of Rights

Source: Author, based on the Report of the Great Council’s Human Rights Commission (personal rights) of 2 May 2022 (supra note 3, pp. 6-9 and 31-32.)

4. Definition and scope of digital integrity

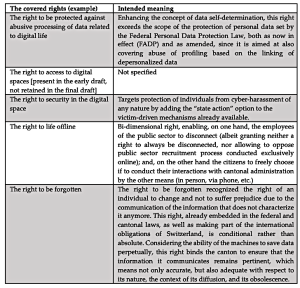

On substance, it was decided to offer more clarity to the novel notion of digital integrity, not yet addressed by the jurisprudence, through the non-exhaustive list providing examples of the rights covered (Figure 5). This – despite the criticism of certain stakeholders consulted, for instance, the University of Geneva, which deemed the proposed level of details excessive, and so – inappropriate in the light of the normative density of the constitutional text and proportionality[10].

Figure 5: Individual rights covered by the notion of digital integrity (examples)

Source: Author’s summary, based on the Report of the Great Council’s Human Rights Commission (personal rights) of 2 May 2022 (supra note 3, pp. 32-33.)

While in part, most of these rights (save for the right to life offline) are already covered by the Swiss federal and Geneva cantonal laws in effect, such as the Federal Data Protection Law[11] or the Geneva Law on public information, access to documents, and protection of personal data[12], it might be argued that the digital integrity context puts a particular emphasis on their selected under-addressed aspects. For instance, explicitly extending protection of privacy to the profiling based on the depersonalized data (under the “abusive” [13] treatment heading); focusing on enabling state actions preventing and addressing cyber-harassment; and emphasizing the canton’s role in ensuring pertinence of the information related to individuals in its possession. In turn, the right to life offline remains somewhat novel in both of its aspects. It is also interesting to note that, in the freedom of choice context, this right is only applicable to the situations involving individuals, with less flexibility afforded to the corporate users of the digital rules, which are encouraged to fully embrace the digital solutions without exceptions.

5. The (future) cantonal efforts in support of realization of digital integrity

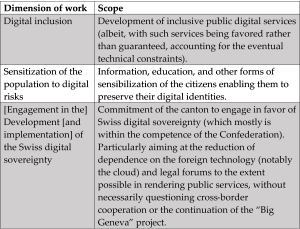

The digital integrity as defined through the examples is further supported by the reference to the work of the canton in the three dimensions, aimed at making it reality (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Direction of the work of the cantonal authorities supporting the realization of digital integrity

Source: Author, based on the Report of the Great Council’s Human Rights Commission (personal rights) of 2 May 2022 (supra note 3, p. 34.)

6. Adequate level of protection in case of treatment of personal data abroad

The provision addressing the processing of personal data abroad subject to assurance of adequate level of protection was further explicitly added in recognition that, at the moment, the canton is not able to ensure the totality of the personal data processing cycle without the resort to the foreign solutions[14]. It is interesting to note that the text, implicitly, extends trust to the Swiss data processing solutions, arguably, even if carried out in different cantons.

7. Automated decision-making (withdrawn)

Meanwhile, the rule addressing automated decision-making, proposed in the earlier draft[15], was removed from the scope in the light of its sufficient coverage by the international law[16], notably the Council of Europe’s Convention for the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data (108+)[17], signed by Switzerland in 2019, to be ratified after the entry into force of the new Swiss Data Protection Law (nFADP 2020)[18] on 1 September 2023 (see Art 9 para 1 letter a) of the treaty).

8. Feedback collected from the principal public law entities of the Canton of Geneva

As a part of refinement of the draft, the department of infrastructure of Geneva’s Council of State has requested comments on potential impact of the new rules on their activities from the principal public law entities of the canton of Geneva (according to the list defined in Art. 3 of the Geneva’s Law on the Organization of the public sector institutions)[19].

Those included the Airport of Geneva, the SIG (Industrial Services of Geneva), the TPG (Geneva Public Transport), the General Hospice, the HUG (University Hospitals of Geneva), the IMAD (Geneva Institution of Home Support), the UNIGE (University of Geneva), and the ACG (Association of Geneva Communes). The feedback so received was made public. It resulted in the expression of the overall support of the digital integrity initiative by the stakeholders concerned. The same, however, have formulated several potential concerns, estimating the implications of the rules on their business[20]. Among those are:

- Novelty and lack of definitions of some among the rights defining the digital integrity, notably, the right to security and the right to be disconnected, which might lead to the emergence of conflicting practices in their application, if no further guidance would be provided;

- Extension of the new rules only to the public law enterprises entrusted with public functions, which might impede their competitiveness with the private entities not subject to the same rules on the markets where no public monopoly exists (such as supply of electricity or gas, telecommunications, etc.[21]);

- Existence of federal laws containing requirements which would not allow the implementation of the right to disconnect, such as the Federal Electricity Supply Act[22], which mandates the use of the smart electricity meters;

- Financial and organizational costs required to maintain “double” (i.e. physical and digital) infrastructure necessary for the implementation of the “freedom of choice” with respect to electronic services concept under the right to disconnect;

- Persisting unclarity about good practices in the non-abusive use of personal data, and necessity to develop Codes of practice for further guidance;

- A delicate balance between the necessity to feed data into the algorithms enhancing efficiency of the services, customer customization, or meeting sustainability concerns (such as reducing carbon emissions) and use of personal or non-personal data (including via profiling);

- Lack of clarity around the scope of the professional activity for the purposes of the civil servants – related aspect of the right to disconnect;

- Limited options for treatment of personal data without the resort to foreign solutions, due to the scarce national offer of the “Infrastructure as a Service” (IaaS) solutions, among others;

- Potential difficulties with implementation of the right to forget, for instance, with respect to medical data, which is stored and processed in a decentralized manner; and

- Existing normative frameworks already covering many of the issues addressed by the new rules in place.

Despite undeniable symbolic significance of the new fundamental right, the above issues appear to support doubts about its practical implications, some of which are already preempted by the existing disciplines, while others, such as ensuring full data processing cycle on the Swiss soil and having resort to the nationally developed tech only, are not [yet] technologically achievable.

Similar initiatives elsewhere

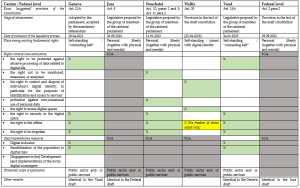

The interest in regulating digital integrity is demonstrated by the Swiss French-speaking cantons, which have launched the dedicated legislative initiative driven by the submission of the members of their parliaments, rather than public initiatives in late 2022 – early 2023, having been inspired by the example of Geneva. A proposal to amend the federal constitution accordingly was also submitted at the Swiss Federal level. (Figure 7). Unlike the cantonal initiatives, this one, if pursued, might have a broader regulatory scope, creating rules which would also bind businesses.

These new initiatives find themselves at the early stages of consideration; occasionally diverge in detail; and are representative of less than 20% of the Swiss cantons, which makes prospects of introduction of the federal digital integrity disciplines in the near future unlikely. To add, despite the joint efforts aimed at developing better understanding of digital sovereignty initiated by the French-Speaking cantons, joined by Tessin, via the Latin Conference of digital directors (CLDN[23]), which has recently supported the preparation of the 3 digital cloud background papers[24], only 2 of the 6 initiatives, those of Geneva and Vaud (amounting to the mirror reflection of the earlier) explicitly speak about digital sovereignty as a mean to support the Swiss digital integrity implementation.

Meanwhile, the implementation costs of guaranteeing digital integrity, even if in its partial (i.e. only applicable to the public sector) version, might be prohibitive for its adoption by the other, especially developing, countries.

Figure 7: Digital integrity legislative initiatives in the selected Swiss Cantons and on the Federal Level

Source: Author, based on the Report of the Great Council’s Human Rights Commission (personal rights) of 2 May 2022 (supra note 3, varied instances) and varied cantonal and federal sources [25].

The interim lessons learned

While the work on Geneva’s digital integrity discipline is still in progress, several trends could already be traced and lessons learned be formulated from its advancement up to date:

- [Swiss] citizens have high appetite for more protection from the state when engaging in the digital interactions and, arguably, for the additional capacity building in the area.

- The public sector stakeholders including the Great Council, the Council of State, Cantonal Commissioner on Data Protection and Transparency[26], as well as the principal public sector entities of the Canton have shown readiness and capacity to maintain a meaningful well-informed discussion over a technical matter, including through the reference to the use cases and the issues arising therein.

- The notion of digital integrity is yet to be shaped and its practical utility (including a value added as a self-standing phenomenon) is yet to be proven. The work in this direction should be expected as soon as the implementation would start, subject to judicial control (leading to the rule-polishing via the jurisprudence). To ensure a meaningful impact, It might appear necessary to expand the effect of digital integrity to also cover the private sector solutions.

- The strong inclination of the canton of Geneva (echoed by the canton of Vaud) towards the Swiss digital sovereignty is clear, even if its feasibility, in the near future, appears to be uncertain. Nevertheless, a nuanced approach, allowing for the necessary cross-border cooperation in cases such as the “Big Geneva” agglomeration[27], should be expected. It remains to be seen if a more advanced level of the “cantonal digital sovereignty” would become the objective next, when feasible,

- Even if aligned with the international digital rule-making approaches, which exempt the public sector from the scope of the rules, for instance, with respect to the restrictions on cross-border data flows and data localization, different rulebooks applicable to the state-trading and privately-owned entities in the areas where they compete on the market risk to erode the competition leading to inefficiencies which might necessitate subsequent state intervention addressing the distortions;

- Finally, it remains to be seen what externalities on the global digital order, with which it is naturally interconnected, the Geneva’s regulation would generate, once implemented.

References and Sources

[1] Constitution of the Republic and Canton of Geneva (Cst-GE) of 14 October 2012 (status on 6 March 2023), in French, available at https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/2013/1846_fga/fr, last accessed on 20 June 2023.

[2] Public vote of 18 June 2023, final cantonal results, Constitutional Law on Protection in Digital Space (“Do you accept the constitutional law modifying the constitution of the Republic and canton of Geneva (For the strong protection of the individual in digital space) (A 2 00 – 12945), of 22 September 2022, in French, available at https://www.ge.ch/votations/20230618/cantonal/4/, last accessed on 20 June 2023.

[3] Report of the Great Council’s Human Rights Commission (personal rights) responsible for studying the draft constitutional law […] amending the constitution of the Republic and canton of Geneva (Cst-GE) (A 2 00) (For strong protection of the individual in digital space) of 2 May 2022, in French, available at https://ge.ch/grandconseil/data/texte/PL12945A.pdf, last accessed on 20 June 2023.

[4] Cantonal Explanatory Brief for the referendum of 18 June 2023, in French, available at https://www.ge.ch/votations/20230618/doc/brochure-cantonale.pdf, last accessed on 20 June 2023.

[5] Supra note 1, Art. 41 para 2.

[6] Supra note 3, p. 9.

[7] Supra note 3, pp. 12-13.

[8] Chancellery of the Republic and canton of Geneva, launch of a cantonal constitutional law initiative entitled: “Yes to strong protection of the individual in the digital space”, of 15 September 2020, in French, available at https://www.fer-ge.ch/documents/37150/129639/179-FAO-20200915.pdf/c5fece4d-0220-1ace-2c4a-9572a4478511?t=1617017831359, last accessed on 20 June 2023, and Signature Collecting form in support of the cantonal constitutional law initiative entitled: “Yes to strong protection of the individual in the digital space”, in French, available at https://www.plr-ge.ch/uploads/ge-1601975728-VkXux.fdebd7d4898326d5179522ed744baac2.pdf, last accessed on 20 June 2023.

[9] Supra note 3, p. 2.

[10] Supra note 3, p. 56.

[11] Swiss Federal Act on Data Protection (FADP) of 19 June 1992 (Status as of 1 March 2019), available at https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/1993/1945_1945_1945/en, last accessed on 20 June 2023.

[12] Geneva Law on Public information, access to documents, and personal data protection of 5 October 2021, in French, available at https://silgeneve.ch/legis/data/rsg/rsg_a2_08.htm?myVer=1657290413670, last accessed on 20 June 2023.

[13] According to the discussion reflected in the Great Council’s Human Rights Commission’s Report, the term “abusive” appears to mainly refer to the “profiling” based on depersonalized data practices, which escape the scope of protection of the personal data protection legislation in effect. Supra note 3, p. 12.

[14] Supra note 4, p. 49.

[15] Supra note 3, p. 29.

[16] Supra note 3, pp. 34-35.

[17] Council of Europe’s Convention for the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data (108+), 2018, available at https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2014_2019/plmrep/COMMITTEES/LIBE/DV/2018/09-10/Convention_108_EN.pdf, last accessed on 20 June 2023.

[18] New Federal Act on Data Protection (nFADP), 2020, available at https://www.kmu.admin.ch/kmu/en/home/facts-and-trends/digitization/data-protection/new-federal-act-on-data-protection-nfadp.html, last accessed on 20 June 2023.

[19] In the understanding of the Art. 3 of the Cantonal Law on the Organization of the Public Law Institutions, in French, available at https://ge.ch/grandconseil/data/odj/010406/L11391.pdf, last accessed on 20 June 2023.

[20] Supra note 3, pp. 36-59.

[21] Supra note 3, p. 41.

[22] Swiss Law on electricity supply of March 23, 2007 (Status on January 1, 2023), available at https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/2007/418/fr, last accessed on 20 June 2023.

[23] https://cldn.ch/, last accessed on 20 June 2023.

[24] These reports are: The study on the opportunities of the sovereign cloud, in French, available at https://cldn.ch/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/CLDN_Etude_cloud_souverain.pdf, Digital Sovereignty, multidisciplinary study, in French, available at https://cldn.ch/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Souverainete-numerique-Etude-pluridisciplinaire.pdf, and the Ethical Analysis of the Sovereign Cloud, available at https://cldn.ch/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Analyse-cloud-souverain_ethix.pdf, all last accessed on 20 June 2023.

[25] Republic and canton of Jura, list of parliamentary initiatives, in French, available at https://www.jura.ch/PLT/Interventions-parlementaires-deposees/Initiatives-parlementaires.html, Initiative No. 38; Great Council of Neuchatel, project of the Decree amending the Constitution of the Republic and Canton of Neuchâtel (Cst.NE) (For a right to digital integrity and the protection of a right to an offline life), of 12 January 2023, in French, available at https://www.ne.ch/autorites/GC/objets/Documents/ProjetsLoisDecrets/2023/23108.pdf; Draft constitution of the canton of Wallis of 25 April 2023, in French, available at: https://www.vs.ch/documents/3914032/23491223/2023-04-25_CONSTITUANTE_Projet+FINAL+%2825+avril+2023%29.pdf/efd61e88-ff75-d637-ccdb-fa1a009f96de?t=1682498019134&v=1.0; Great Council of the Canton of Vaud, Initiative – 23_INI_2 – Patricia Spack Isenrich et al – Let’s protect our digital integrity, in French, available at https://www.vd.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/organisation/gc/fichiers_pdf/2022-2027/23_INI_2_depot.pdf; Federal Assembly (Swiss Federal Parliament), Parliamentary Initiative 22.479, “Introduce in the Constitution the right to digital integrity”, available at https://www.parlament.ch/fr/ratsbetrieb/suche-curia-vista/geschaeft?AffairId=20220479, all – last accessed on 20 June 2023.

[27] Supra note 3, p. 34.